My ten minute talk from the BSA Postgraduate Day, 5th April 2016 on a panel about ‘Rebellious Sociology’*

What I want to do in my 10 mins is to explore another possible route through what Dave Beer has termed ‘punk sociology’. Taking a punk ethos, perhaps best encapsulated in this cartoon from the Sniffin Glue fanzine this cartoon from the Sniffin Glue fanzine, punk sociology called for a similar boldness among sociologists in order to reinvigorate the discipline.

punk sociology called for a similar boldness among sociologists in order to reinvigorate the discipline.

The book’s central argument is that ‘the attitude and sensibility of punk can productively be used to regenerate and energise the sociological imagination’. Beer argues that the lessons that can be learned for sociology from the punk attitude are: DIY ethic, the breakdown of barriers between audience and band, and open-ness to other music.

When reading the book, which I like, it struck me that feminism has being doing punk sociology for a long time and that isn’t really explored in the book. Also, if you read Viv Albertine (of The Slits) book, the experience of women in the 1970s punk movement doesn’t chime with this idealistic rendering – but that second point is for another day.

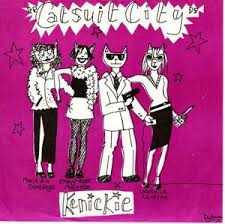

My take on punk sociology comes through a different lineage. It comes filtered through the riot grrrl movement of the 1990s which inspired me and my friends to form a band when I was 15. Riot grrrl took punk’s DIY spirit – which manifested, for example, in the fanzine culture, mode of production and aesthetic (see our debut single on the left, I’m the cat in the feather boa) – but fostered a more communal approach to music making and  doing. It had feminist politics at its core, as encapsulated in the shout ‘girls to the front’. When my teenage band got together we couldn’t play our instruments but we learned how to play together, through learning from each other. The reason we felt equipped to form a band had a lot to do with a DIY sensibility that valued creativity over technical proficiency.

doing. It had feminist politics at its core, as encapsulated in the shout ‘girls to the front’. When my teenage band got together we couldn’t play our instruments but we learned how to play together, through learning from each other. The reason we felt equipped to form a band had a lot to do with a DIY sensibility that valued creativity over technical proficiency.

Collaboration – and feminism in the face of a male-dominated music scene – was absolutely key to this and that is something I want to emphasise here, following on from Hannah [who was speaking just before me of the need for non-heroic sociology and about when to speak up in public debate].

Feminist collaboration and collective working strikes me as a quiet kind of rebellious – and unheroic – sociology. I think it is important because of the individualising times we live in, both in universities and beyond. Firstly, following on from Hannah, we are encouraged by the current academic system to market ourselves as lone wolf heroic researchers in order to get jobs, to be ESRC ‘Future Research Leaders’ or British Academy ‘Rising Stars’, or even Harvard ‘Geniuses’. This is all a very individualistic and potentially seductive model of doing research. Yet some of the best work is done collaboratively. I think it’s politically important within sociology to argue for collaboration and to present collaborative work as such and not parcel it up in individual packages for the sake of presentation.

The times we are living through require sociologists to operate in different kinds of temporalities at once. Kirsteen Paton captures this beautifully in her blog for the Sociological Review on ‘getting real’ where she suggests sociologists learn from the fast organising of those who are currently resisting and use the tools we have to hand – this echoes Les Back and Nirmal Puwar’s call for ‘live methods’ for sociology that intervene in real time. We have to be quick-footed as researchers and this can often be more effectively done through collaboration with other academics and with other groups.

Two examples: the first comes from a collaborative piece of work conducted by Kirsteen, with Gerry Mooney and Vikky McCall. Kirsteen writes about approaching East End residents in Glasgow to talk about the possibility of applying for funding to study the impact of the Commonwealth Games:

‘I was swiftly put right when they replied ‘no offence, but we’d rather not have a research event like this after the fact telling us that we got displaced by the Games’. Bingo. They saw limitations of academic practice before I had. The speed of response required to understand social issues is not matched by that of funding processes. Yet I was able to get some funds through collaboration with a colleague Gerry Mooney at the Open University. This gave us enough money to buy diaries, and we asked residents to record their thoughts and day-to-day experiences of the Games. Another colleague on the project, Vikki McCall, lives in the East End and was on the ground keeping fieldwork going, popping round collecting diaries, texting participants. We even held our research meetings in Vikki’s living room; really DIY. And the beauty of the diaries and blog was that they captured how residents’ thoughts and feelings evolved in relation to their experiences of the Games. They made choices about what to report and how, such as including unsolicited photos and even poems. This DIY became a kind of co-production which produced a snapshot of everyday life in austerity Britain.’

This co-production was between the participants and the team of three. One practical reason for working collaboratively like this is it allows us to do the work that needs to be done, at the time when it needs to be done, without creating a huge workload for one person. It allows us to think on our feet and to respond.

The second example comes from a piece of work I have been involved in on ‘Mapping Immigration Controversy’. The initial impetus for this research was a Twitter conversation about what we as sociologists could do in the face of ‘Operation Vaken’ a Home Office initiative that involved immigration checks at public transport hubs and what became known as the #racistvan, the van mounted with the board reading ‘In the country illegally? Go home or face arrest’. In order to capture what people on the street thought about these interventions, an assortment of academics and activists got together and constructed and carried out a survey. Again, this was a fast response to an unfolding event. Following this, Hannah saw the new call for the ESRC ‘Urgent Grants’, marking a realisation by the funders that some research is time sensitive, perhaps. Some of us put together a proposal, working in partnership with community groups from the outset, and were successful.

We not only carried out that research together but have collaborated on a bunch of other things including a blog which tracked our research as we carried it out, public events, and we are currently finishing a book. We also commissioned a film to represent our findings.

The digital age makes it really easy to both collaborate and communicate results in different kinds of ways. I was recently inspired by an example of old school DIY – a pamphlet – but which is also circulating online.

This example comes from SARF‘s research and is based on a project examining stigmatisation and economic marginalisation of ‘white working class people in Salford and Manchester’. As well as a long research report, those involved wanted to produce something that could circulate in a different way and that was more immediate, taking inspiration from Emory Douglas, the artist of the Black Panthers. You can read more about how this booklet was generated through workshops here.

Present conditions conjure competition and individualisation among academics. I’m not suggesting people don’t apply for individual fellowships with embarrassing labels or sell themselves as a ‘rising star’ in a job interview situation. The problem is when we start believing those stories that we tell about ourselves. In order to produce the kind of research that is vital for the times we will need to work together and resist this.

Post-script

Later on, after this talk, I learned via Twitter of #ResSisters, a collective of early career feminist researchers who are challenging individualised modes of production in the contemporary university – and crucially speaking up about the ways in which these modes are gendered. You can read and watch Victoria Cann’s Pecha Kucha on this here. The first point on their manifesta is ‘Embrace collectivity and embrace allies’.

This attitude also comes out very strongly in Les Back’s new book Academic Diary where Les discusses learning from feminism of the importance of ‘trading envy for admiration’. As my friend that works in fashion says ‘three is a trend’ so maybe we are all on to something here…

*I had written out the first part of this talk and free-styled the second half so the words might not be exactly the same as those used on the day…

doing. It had feminist politics at its core, as encapsulated in the shout ‘girls to the front’. When my teenage band got together we couldn’t play our instruments but we learned how to play together, through learning from each other. The reason we felt equipped to form a band had a lot to do with a DIY sensibility that valued creativity over technical proficiency.

doing. It had feminist politics at its core, as encapsulated in the shout ‘girls to the front’. When my teenage band got together we couldn’t play our instruments but we learned how to play together, through learning from each other. The reason we felt equipped to form a band had a lot to do with a DIY sensibility that valued creativity over technical proficiency.